On November 2, 2003, Anick Jesdanun of the Associated Press reported that the ``Internet [is] littered with abandoned sites'' [20]. The story was picked up by many news outlets from USA's CNN to Singapore's Straits Times. The article further states that

``[d]espite the Internet's ability to deliver information quickly and frequently, the World Wide Web is littered with deadwood - sites abandoned and woefully out of date.''

Of course this is not news to most net-denizens, and speed of delivery has nothing to do with quality of content, but there is no denial that the increase in the number of outdated sites has made finding reliable information on the web even more difficult and frustrating. Part of the problem is an issue of perception: the immediacy and flexibility of the web create the expectation that the content is up-to-date; after all, in a library no one expects every book to be current, but on the other hand, it is clear that books once published do not change1, and it is fairly easy to find the publication date.

While there have been substantial efforts in mapping and understanding

the growth of the

web (see, for example, [9]),

there have been fewer investigations of its death and decay.

Determining whether a URL is dead or alive is quite easy, at

least in a first approximation (see below), and in fact, it is

known that web pages disappear at a rate of 0.25-0.5%/week [16]. However

determining whether a page has been abandoned it is much more

difficult.

Our main goal in this paper is to start understanding and quantifying

this problem: how can we determine that a page has been abandoned, or

that it is no longer well-maintained, in other words has the page

decayed? How widespread is the web decay? Assuming that decay can

be

measured how can we use this knowledge?

A human might use obvious clues: a page offering precautions for Year 2K, a page that urges people to vote for someone in the 2002 elections, a page where ``next week'' refers to times long gone, a page were most links do not work, are obvious clues. However except for the last, none of these is easily ``readable'' by a machine. We are facing an issue similar to the classic Information Retrieval problem: there, one must find ``signals'' that a program could use to determine whether a page is relevant to a given query; here, we need ``signals'' to determine whether a page has decayed or not. In both cases the signals are noisy--what we are trying to find is a correlation.

Dead links

Dead links are the clearest giveaway to the obsolescence of a

page. Indeed, this phenomenon of ``link-rot'' has been studied in

several areas--for example, Fetterly et al. [16] in

the context of web research, Koehler [22,23] in the

context of digital libraries, and Markwell and Brooks [26,27] in the context of biology

education. However using the

proportion of dead links as a decay signal, presents two problems, one

``fix-able'', one not.

(1) The first problem is that of determining whether a link is ``dead''

is

not trivial. According to the HTTP protocol [17]

when a request is made to a server for a page that is no longer

available,

the server is supposed to return an error code, usually the infamous

404. (This code is so popular that ``has gone 404'' meaning

``gone

and cannot be found'' seem to have entered the vernacular.) As we

discuss in Section 3, in

fact many servers, including most reputable

ones, do not return a 404 code--instead the servers return a

substitute page and an OK code (200). The substitute page sometimes

gives a written error indication, sometimes is a redirect to the

original domain home page, and sometimes has absolutely nothing to do

with the original page. Our study shows that these type of

substitutions, called ``soft-404s'' account for more than 25% of the

dead links. We discuss this issue in detail in Section 3

and propose a heuristic for the detection of servers that engage in

soft 404s.

The heuristic is effective for all cases except for one special case:

a dead domain home page bought by a new entity and/or ``parked'' with

a broker of domain names: in this special case we can determine that

the server engages in soft 404 in general but there is no way to know

whether the domain home page is a soft 404 or not.

(2) The second problem of dead links as a decay signal, is that this is

a

very noisy signal. One reason is because it is easy to manipulate.

Indeed, many commercial sites use content management systems and

quality check systems that automatically remove any link that results

in a 404 code. For example, our experiments indicate that the Yahoo!

taxonomy is continuously purged of any dead links (See Section 5.4).

However, this is hardly an indication that every piece of the Yahoo!

taxonomy

is up-to-date.

Another reason for the noisiness is that pages of certain types tend to live ``forever'' even though no one maintains them: a typical example might be graduate students pages--many universities allow alumni to keep their pages and e-mail addresses indefinitely as long as they do not waste too much space. Because these pages link among themselves at a relatively high rate, they will have few dead links on every page, even long after the alumni have left the ivory towers; it is only as we look at a larger radius around these pages that we start noticing a surfeit of dead links.

Our contributions

The discussion above suggests that the measure of the decay of page p

should depend not only on the proportion of dead pages at distance 1

from p but also, maybe

to a decreasing extent, on the proportion of

dead pages at distance 2, 3, and so on.

One way to estimate these proportions is via a random walk from p: at every step if we land on a dead page we declare failure, otherwise with probability σ we declare success, and with probability 1 - σ we continue the walk. We define the decay score of p, denoted D(p) as the probability of failure in this walk. Thus the decay score of a page p will be some number between 0 and 1.

At first glance, this process is similar to the famous random surfer

of PageRank [7]; however, they

are quite different in

practice: for PageRank the importance of a page p depends

recursively on the importance of the pages that point to p.

In contrast the decay of p

depends recursively on the decay of the

pages that are linked from p.

Thus, computing the underlying

recurrence once the web graph is fully explored and represented is

very similar, but

It is generally agreed that PageRank is a better signal for the quality of a page than simply its in-degree (i.e., the number of pages that point to it) and recent studies [29,10] have shown that the in-degree has only limited correlation with PageRank. Similar questions can be asked about the decay number versus the dead links proportion: our experiments indicate that their correlation is only limited and indeed the decay number is a better indicator. For instance, on average, the set of 30 pages that we analyzed from the Yahoo! taxonomy have almost no dead links, but have relatively high decay, roughly the median value observable on the Web. This seem to indicate that Yahoo! has a filter that drops dead links immediately, but on the other hand the editors that maintain Yahoo! do not have the resources to check very often whether a page once listed continues to be as good as it was.

Organization of this paper

In Section 2 we

discuss related work in further detail. In Section 3 we address

the problem of identifying dead pages despite soft 404 servers. In

Section 4 we provide a

rigorous definition of

the decay measure and give algorithms for its computation. In

Section 5 we present and

interpret our experiments. In

Section 6, we conclude

the paper with a discussion of potential applications of the decay

measure.

The related work falls into four categories. The first is the study of dead links on the web, and more generally the evolution of web pages. The second is link analysis. The third is the use of random walks in web algorithmics. The fourth is the study of theoretical graph models for the web.

As we mentioned in the Introduction, there have several studies analyzing the so-called ``link-rot''. A large study of the evolution of web pages was done by Cho and Garcia-Molina [13] and this study was expanded substantially by Fetterly et al. [16]. The latter studied millions of web pages over a period of time and reported statistics including dead link count, etc. Very recently Ntoulas et al. [28] studied page changes (including link structure) in 154 popular web sites. The rate of change within web pages and implication for crawling and caching policies were studied in [13,6,31,14].

Koehler [22,23] studies web attrition in the context of digital libraries and reports statistics including dead link rate. Markwell and Brooks [26,27] study the link rot phenomenon in the context of biology education. As we noted earlier, the ``Internet deadwood'' has been ``discovered'' by the popular media.

The graph structure of the Web has been used extensively in Web IR work. In particular the HITS algorithm of Kleinberg [21] and the PageRank algorithm of Brin and Page [7] have been widely studied. Improvements to HITS were obtained by Bharat and Henzinger [5] and Chakrabarti et al. [11]. There have been numerous subsequent modifications and enhancements to the algorithmic implementation of the basic PageRank algorithm--in this version of the paper, we do not attempt to list these references. The one that is most relevant to us is the recent work of Haveliwala [18], who developed the notion of topic-sensitive PageRank; the PageRank notion is refined to reflect the relevance of a page to a topic. However, as we discussed in the Introduction, PageRank and its variation are quite different from our decay score.

Random walks are quite popular to compute various web statistics. For instance, Bar-Yossef et al. [2] used random walks to approximate aggregate queries about web pages. Henzinger et al. [19] and subsequently, Rusmevichientong et al. [30] used random walks to uniformly sample URLs.

Finally, developing models to capture the evolution and characteristics of the web graph has been an active area of research. See, for example, [3,25,1]. These models primarily address the growing aspect of the web. To the best of our knowledge, there are no graph models that strive to explicitly include the decay and death of pages within the graph model, although as we already mentioned, the birth, change, and death of pages in isolation has been examined in detail. We hope that our study will stimulate research to produce web graph models that correlate well with the experimental data that we present here.

A dead page is a page that is not publicly available over the web. A page can be dead for any of the following reasons: (1) its URL is malformed; (2) its host is down or non-existent; or (3) it does not exist on the host. The first two types of dead pages are easy to detect: the former fail the URL parsing and the latter fail the resolution of the host address. When fetching pages that are not found on a host, the web server of the host is supposed to return an error; typically, it is the (in)famous 404 HTTP return code. However, it turns out that many web servers today (see Section 5.2 for statistics) do not return an error code even when they receive HTTP requests for non-existent pages. Instead, they return an OK code (200) and some substitute page; typically, this substitute is an error message page or the home-page of that host or even some completely unrelated page. We call such non-existent pages that behave as above ``soft-404 pages''.

The existence of soft-404 pages makes the task of identifying dead pages non-trivial. We next describe our algorithm for this task. The pseudo-code of the algorithm is given below. For the rest of the discussion we identify a page with its URL and use the two notions interchangeably.

Function bool isDeadPage(u)

in: URL u

1: string Tu,Tr, int Ku, Kr, bool error

2: fetch(u, wu, Tu, Ku, error)

3: if (error) then // A hard-404

4: return true

5: URL r := u.PARENT + 25 random characters

6: fetch(r, wr, Tr, Kr, error)

7: if (error) then // host returns a hard-404 on dead pages

8: return false

9: if (u is the root of u.HOST) then

10: return false // a root cannot be a soft-404

11: if (Ku ≠ Kr) then // different number of redirects

12: return false

13: if (wu = wr) then // same redirects & same number of redirects

14: return true

15: if (shingle(Tu) = shingle(Tr)) then // almost-identical content

16: return true

17: return false // not a soft-404 page

Function fetch(u, Tu, wu, Ku, error)

in: URL u

out: string Tu, URL wu, int Ku, bool error

1: wu := u

2: Ku := 0

3: set〈URL〉 redirects

4: redirects.insert(u)

5: while (true) do

6: URL v, bool redirect

7: atomicFetch(wu, Tu, v, redirect, error)

8: if (error) then

9: return // A hard-404

10: if (! redirect) then // no more redirects

11: return

12: if (redirects.find(v)) then // a redirect loop

13: error = true; return

14: if (Ku ≥ 20) then // too many redirects

15: error = true; return

16: wu := v, Ku := Ku + 1

17: end while

Function atomicFetch(w, T, v, redirect, error)

in: URL w

out: string T, URL v, bool redirect, bool error

1: parse(w, error)

2: if (error) then // parse URL failed

3: return

4: IPAddress address

5: getIPAddress(w.HOST, address, error)

6: if (error) then // resolution of host's IP address failed

7: return

8: HTTPRetCode code

9: httpGet(address, T, v, code, timeout = 10sec, error)

10: if (error) then // http get timed out

11: return

12: if (code ∈ { 403, 404, 410, 5xx} ) then // bad http return code

13: error := true; return

14: if (code ∈ { 3xx }) then

15: redirect := true

16: else

17: redirect := false

Loosely speaking, a soft-404 page is a non-existent page that does not return an error code. In contrast a hard-404 page is a non-existent page that returns an error code of 403, 404, or 410, or any code of the form 5xx (see [17] for a list of all error codes). Dead pages consist of soft-404 pages, hard-404 pages, and a few more cases such as time-outs and infinite redirects discussed below.

Let u be the URL of a page, to be tested whether dead or alive. Let u.HOST denote the host of u, and let u.PARENT denote the URL of the parent directory of u. For example, both the host and the parent directory URL of http://www.ibm.com/us are http://www.ibm.com; however the parent directory of http://www.ibm.com/us/hr is http://www.ibm.com/us. u.HOST and u.PARENT can be extracted from u by a proper parsing.

Our algorithm starts by trying to fetch u from the web (Line 3 of the function isDeadPage). A fetch (see function atomicFetch) may result in one of the following three outcomes: (1) it succeeds, (2) it fails, or (3) it redirects to a different URL v. The possible reasons for a failure are: (a) u is an invalid URL and could not be properly parsed (Lines 2-3 of atomicFetch); (b) the local DNS server could not resolve the IP address of u.HOST (Lines 6-7 of atomicFetch); (c) when creating a connection to u.HOST, there was no response within T seconds (in our experiments we choose T = 10) (Lines 10-11 of atomicFetch); or (d) the web server of u.HOST returns an error HTTP return code in response to the request for u (Lines 12-13 of atomicFetch). The HTTP return codes which we consider as error are 403 (Forbidden), 404 (Not found), 410 (Gone), and all the codes of the form 5xx (Server errors). A success is a HTTP return code in the 2xx series or 4xx series (except for 403,404,410), and a redirect is indicated by an HTTP return code in the 3xx series.

Clearly when the fetch fails, the page is dead. We now discuss how to analyze the two other cases (success or redirect). The redirect case is also rather simple. Our algorithm attempts to fetch u. If it redirects to a new URL v, it then attempts to fetch v. It continues to follow the redirects, until reaching some URL wu, whose fetch results in a success or a failure (see the function fetch). (A third possibility is that the algorithm detects a loop in the redirect path (Lines 12-13 of fetch) or that the number of redirects exceeds some limit L, which we chose to be 20 (Lines 14-15 of fetch); in such a case the algorithm declares u to be a dead page, and stops.) If the fetch of wu results in a failure, u is declared a dead page as before. If the fetch results in a success, the algorithm proceeds to checking whether u is a soft-404 page.

Detecting soft-404 pages

The algorithm detects whether u

is a

soft-404 page or not by ``learning'' whether the web server of u.HOST

produces soft-404 at all. This is done by asking for a page r, known with high probability not

to exist on u.HOST.

It then

compares the server behavior when asked for r,

with its behavior when asked for u.

The first question to be addressed is how to come up with a page r that is guaranteed not to exist on u.HOST. We do this as follows: we choose a URL, which has the same directory as u, and whose file name is a sequence of R random letters (in our experiments we choose R = 25; see Line 5 of isDeadPage). The URL r is simply the concatenation of the URL u.PARENT with the random sequence. Since the file name is chosen at random, the probability that it exists under that directory is at most N/26R, where N is the number of files that do exist under the directory. For any reasonable value of N, this probability is tiny, and thus we can safely assume that the random page r does not exist.

The reason to choose r to be in the same directory as u (and not as a random page under u.HOST) is that in large hosts different directories are controlled by different web servers, and therefore may exhibit different responses to requests for non-existent pages. An example is the host http://www.ibm.com. When trying to fetch a non-existent page http://www.ibm.com/blablabla, the result is a 404 code. However, a fetch of http://www.ibm.com/us/blablabla returns the home-page http://www.ibm.com/us. Thus http://www.ibm.com/us/blablabla is a soft-404 page, but http://www.ibm.com/blablabla is a hard-404 page.

Next we need to compare the behavior of the web server on r with its behavior on u. Let wr and wu denote the final URLs reached when following redirects from r and u, respectively.

Let Tr and Tu denote the contents of wr and wu, respectively. Let Kr and Ku denote the number of redirects the algorithm had to follow to reach wr and wu, respectively.

If the fetch of wr results in a failure, we conclude that the web server does not produce soft-404 pages. Since the fetch of wu succeeded, the algorithm can safely declare u as alive (Lines 7-8 in isDeadPage). Suppose, then, that the fetch of wr results in a success. Thus, r is a soft-404 page.

If wr = wu and Kr = Ku, then u and r are indistinguishable. This gives a clear indication that u is a soft-404 page except for one special cases: there are situations when soft-404 pages and legitimate URLs both redirect to the same final destination (e.g., to the host's home-page). A good example of that is the URL http://www.cnn.de (the CNN of Germany), which redirects to http://www.n-tv.de; however, also a non-existent page like http://www.cnn.de/blablabla redirects to http://www.n-tv.de. We thus use the following heuristic: if u is a root of a web site, then it can never be a soft-404 page (Lines 9-10 of isDeadPage; see discussion below about when this heuristic may fail). Otherwise, if wr = wu and Kr = Ku, then u is declared a soft-404 page (Lines 13-14 of isDeadPage).

If Kr ≠ Ku, the algorithm declares u to be alive (even if wr = wu), because the behavior of the web server on u is different from its behavior on r (Lines 11-12 of isDeadPage). An example that demonstrates that the number of redirects is crucial for the test is http://www.eurosport.de/. Fetching http://www.eurosport.de/ incurs two redirects that finally land in a valid page. However, fetching http://www.eurosport.de/blablabla redirects first to http://www.eurosport.de/ and then two more redirects as before. Thus, both the valid page and the soft-404 page end up at the same valid page, but the former requires two redirects while the latter requires three.

Even if wr ≠ wu, it is still possible that u is a soft-404 page, because in some hosts each soft-404 page is redirected into a unique address (http://www.amazon.com, for example). We thus next look at the contents of wr and wu, and at the parameters Kr, Ku. If wr ≠ wu, Kr = Ku, and Tu and Tr are identical or nearly-identical (near-identity can be checked via shingling [8]), the algorithm declares u to be a soft-404 page (Lines 15-16 of isDeadPage). Note that testing near-identity (as opposed to complete identity) may be important, because sometime the web server embeds the non-existing URL u in the text of the page it returns or does other minor changes.

The above scheme is doing its best to capture as many of the cases of soft-404 pages as possible. It is not flawless though. The main weakness is in the heuristic that asserts roots of web sites can never be soft-404 pages. An emerging phenomenon on the web is the one of ``parked web sites''. These are dead sites whose address was re-registered to a third party. The third party (typically, a porn site owner) puts a redirect from those dead sites into his own web site. The idea is to profit from the prior promotional works of the previous owners of the dead sites. A report by Edelman [15] gives a nice description of this phenomenon as well as a case study of a specific example.

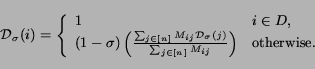

Let n be the total number of pages. Let D ⊂ [n] be the set of all dead pages, and let all other pages be live. Let M be the n x n matrix of the multi-graph of links among pages, so that Mij is the number of links on page i to page j. To begin, we perform one modification to the matrix: M ← M + I, adding a self loop to each page. We will define a measure Dσ(i) in terms of a ``success parameter'' σ ∈ [0, 1]. (In our experiments, we take σ = 0.1.)

We begin by describing decay as a random process, and argue that it captures the intuition that we seek. Next, we give a formal recursive definition, and finally, we cast it as a random walk in a Markov chain.

A process for computing decay

The measure can be seen as a random process governing a ``web

surfer,'' as follows. Initially, the current page p is

set

to i, the page whose decay we are computing. The surfer at the

current page will perform the following steps, eventually returning a

binary decay score depending on the random choices made during

execution of the steps; the process therefore defines a distribution

over {0, 1}. The decay Dσ(i)

is the mean of this distribution.

Unrolling this definition a few steps, it becomes clear that the decay of a page is influenced by dead pages a few steps away, but that the influence of a single path decreases exponentially with the length of the path. For example a dead page has decay 1, a live page whose outlinks are all dead has decay 1 - σ, a live page whose all outlinks point to live pages that in turn point only to dead pages has decay (1 - σ)2, etc.

A formal definition of the decay measure

Recursively, we can define

Dσ(i) as follows:

Understanding the solution to this recursive formulation is easiest in the context of random walks, as described below.

Decay as a random walk with absorption

Decay scores may also be viewed as absorption probabilities in a

random walk. We now define the Markov chain in which this walk takes

place. First, the incidence matrix of the web graph must be

normalized to be row stochastic (each nonzero element is divided by

its row sum). Next, two new states must be added to the chain, each

of which has a single outlink to itself: n+1

is the success state,

and n+2 is the failure state.

Thus these two new states are

absorbing. Finally, we make the following two modifications to the

matrix: first,

each dead state is modified to have a single outlink with probability

1 to the failure state; second, all edges from non-dead states ( [n] \ D) are multiplied by 1 - σ

in probability, and a new

edge with probability σ is added to the success

state. Hence

the two new states are the only two absorbing states of the chain, and

any random walk in this chain will be eventually absorbed in one of

the two states. Walks in this new chain mirror the random process

described above, and the decay of page i is the probability of

absorption in the failure state when starting from state i.

Global static ranking measures such as PageRank [7] usually have to be computed globally for the entire graph during a lengthy batch process. Other graph oriented measures such as HITS [21] may be computed on-the-fly, but require inlink information typically derived from a complete representation of the web graph, such as [4], or from a large scale search engine that makes available information about the inlinks of a page.

Decay, on the other hand, is defined purely in terms of the out-neighbors of i. We make the following observation:

Observation 1 The decay value of a page can be approximated to within constant accuracy in a constant number of HTTP fetches, independent of the link structure of the graph, without access to any other supporting indexes.

Such an implementation mirrors the random process definition of decay given in Section 4.1. Because the walk terminates with probability at least σ at each step, the distribution over number of steps is bounded above by the geometric distribution with parameter σ; thus, the expected number of steps for a single trial is no more than 1/σ, and the probability of long trials is exponentially small. Further, the value of each trial is 0 or 1, and so decay can be estimated to within error ε with probability 1 - δ in ε-2 log (1/δ); steps; this follows from standard Chernoff bounds. (In practice, we employ 300 trials to estimate the decay value of each page.)

Like other measures, decay is also amenable to the more traditional batch computation; we have not tried it but we expect the time required to be similar to the time required by PageRank.

We implemented the algorithm for identifying dead pages and the random walk algorithm for estimating the decay score of a given page. We then ran several sets of experiments described below. The first set of experiments validates that our decay measure is a reasonable measure for decay of web pages. We compare it against another plausible measure, namely, the fraction of dead links on a page. After establishing that our measure is reasonable, we use it to discover interesting facts about the web.

In this section we specify the settings of parameters for our two algorithms that were used in the experiments. The parameters of the algorithm for detecting dead pages were set as follows:

The parameters of the random walk algorithm were set as follows:

On average, getting the decay score of a page took about 7 minutes on a machine with double 1.6GHz AMD processors, 3 GB of main memory, running a Linux operating system and having a 100 Mbps connection to the network. Since our task was highly parallelizable (the decay score of different pages could be estimated in parallel, and also different random walks for the same page could be run in parallel), we ran about 10 random walk processes simultaneously, in order to increase throughput.

Our first experiment involved computing the decay score and the fraction of dead links on 1000 randomly chosen pages. The pages were chosen from a two billion page crawl performed largely in the last four months.

To begin with, of the 1000 pages, 475 were already dead (substantiating the claim that web pages have short half lives, on average). For each remaining page, we computed its decay score as well as the fraction of its dead links. In total, there were 710 dead links on the pages and out of these, 207 were pointing to soft-404 pages (roughly 29%). Moreover, the random walks during the decay score computation of the 525 pages encountered a total of 22,504 dead links, out of which 6.060 pointed to soft-404 pages (roughly 27%). Such a high fraction of soft-404 pages detected by our algorithm should be a further impetus to develop even better algorithms to detect them. Another interesting statistic is that only 350 of the 525 pages alive had a non-empty `Last Modified Date'.

The main statistic emerging out of this experiment is that the average fraction of dead links is $0.068$ whereas the the average decay scores of a live page with at least one outlink are The main statistic emerging out of this experiment is that the average fraction of dead links is 0.0680.168, 0.106, 0.072, and 0.041 for values of σ = 0.1, 0.2, 0.33 and 0.5, respectively.

The decay curves in Figure 1 reflect the fact that for a given page i if σ1 ≥ σ2, then Dσ1(i) ≤ Dσ2(i).

Proof: The decay is the probability of absorption into the failure state. Consider all paths that lead to the failure state. Then the weight of each individual path under σ1 is less or equal to its weight under σ2; namely for a path of length k it is (1 - σi)k times the unbiased random walk weight of the path. (The same argument does not work for the paths that lead to the success state; their individual weight is not monotonic in σ.)

For the rest of the paper we use σ = 0.1.

Clearly the decay and the fraction of dead links are related but not

in a simple way. More precisely, if F(i) is the fraction

of

dead links on page i, and

page i is not dead then

where D'(i) is the average decay of the non-dead neighbors of i.

Figure 1 shows that the distributions of D and F intersect. The difference among them can also be seen from the scatter plot of these distributions for σ = 0.1 (Figure 2). The scatter plot shows that the decay score is generally more than the fraction of dead links. (This also follows from equation 1.) More interestingly, it also shows that the decay measure can be close to 0.5 even when the fraction of the dead links is close to 0.

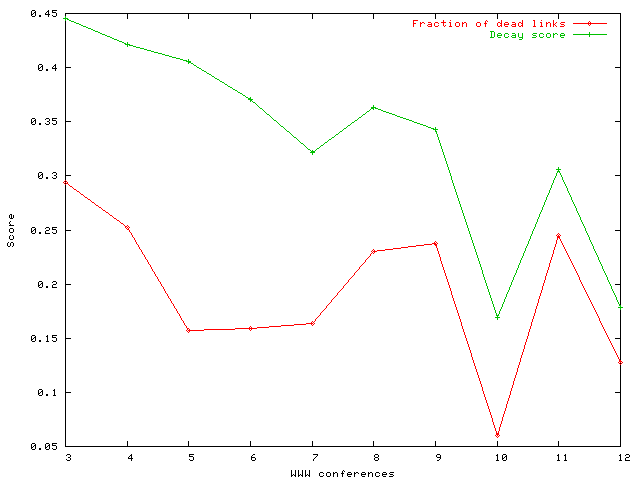

Our next experiments deal with the papers from the last ten World Wide Web conferences. We crawled all the (refereed track) papers from WWW3 to WWW12 and for each paper with at least one outlink, we computed its decay score and the fraction of dead links. The averaged results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Average decay scores and fraction of dead links for papers from the last ten WWW conferences.

The main observation is the following. We claim that the trend exhibited by decay scores is more representative and more useful than that of the fraction of dead links. From the figure, it is evident that the decay scores decline as conferences get more recent; on the other hand, the fraction of dead links exhibits a flatter trend. It is arguably the case that on average, links contained in papers from older conferences not only have a higher chance of themselves being dead, but also are more likely to point to pages that are dead. Decay scores are therefore able to reflect better the temporal aspect of hyperlink creation and maintenance; we believe this feature might have other applications.

Our next experiment consisted of a set of 30 nodes from the current Yahoo! ontology (Figure 4). We chose the nodes so as to have a relatively large number of outside links and be well represented in the Internet Archive (www.archive.org).

We computed the decay score and fraction of dead links for each of the 30 nodes. We then used the Internet Archive to fetch the previous incarnations of the same nodes in the past five years and computed the decay scores and fraction of dead links for these `old' pages as well. Since the archived pages have time stamps embedded in the URL, at the end of this step, we obtained a history of decay scores and fraction of dead links for each leaf. We then averaged these scores over the 30 nodes and bucketed the time line into months (since 1998) to obtain Figure 5.

The behavior of decay scores and fraction of dead links are still different; but the important point is that this difference in behavior is different from that of WWW conferences as well (Figure 3). Unlike in the WWW conference case, here, the decay score is flatter whereas the the fraction of dead links is rapidly decreasing. The behavior of the dead links is as expected--the fraction of dead links is close to 0 in the current version of the Yahoo! nodes; this is obviously due to their automatic filtering of dead links. But, even in the current version of these nodes, the figure shows that the decay score of these is as high as that of a random web page (i.e., close to 0.2).

Thus, we can conclude that many of the pages pointed by Yahoo! nodes, even though are not dead themselves yet, are littered with dead links and outdated. E.g., consider the Yahoo! category Health/Nursing. Only three out of 77 links on this page are dead. However, the decay score of this page is 0.19. A few examples of dead pages that can be reached by browsing from the above Yahoo! page are: (1) the page http://www.geocities.com/Athens/4656/ has an ECG tutorial where all the links are dead; (2) the page http://virtualnurse.com/er/er.html has many dead links; (3) many of the links in the menu bar of http://www.nursinglife.com/index.php?n=1&id=1 are dead; and so on. We believe that using decay scores in an automatic filtering system will improve overall quality of links in a taxonomy like Yahoo!.

Our final set of experiments involves the Frequently asked questions (FAQs) obtained from www.faqs.org. We collected all the 3,803 FAQs and computed the decay scores and the fraction of dead links for each of them. We also computed the last modified/last updated date for the FAQs by explicitly parsing the FAQ (since the last modified date returned in the HTTP header from www.faqs.org does not represent the actual date when the FAQ was last modified/updated). As in the earlier case, we collated the results and bucketed the time line into years since 1992 to obtain Figure 6.

From the figure, it is clear that despite the fact that the FAQs are hand-maintained in a distributed fashion by a number of diverse and unrelated people, it suffers from the same problem--many pages pointed to by FAQs are unmaintained.

We have introduced and formalized the decay measure, compared and contrasted it to the technique of counting number of dead links on a page, and motivated our measure as an approach to capturing subtle but pervasive phenomenon on the web.

We now point out a number of applications areas that we believe could fruitfully apply the decay concept:

(1) Webmaster and ontologist tools: There are a number of tools made available to help webmasters and ontologists track dead links on their sites; however, for web sites that maintain resources, there are no tools to help understand whether the linked-to resources are decayed. Our observation about Yahoo! leaf nodes suggests that such tools might provide an automatic or semi-automatic approach to addressing the decay problem.

(2) Ranking: As far as we know, decay measures have not been used in ranking, but users routinely complain about search results pointing to pages that either do not exist (dead pages), or exist but not reference valid current information (decayed pages). Incorporating the decay measure into the rank computation will alleviate this problem. Furthermore, web search engines could use our soft-404 detection algorithm to eliminate soft-404 pages from their corpus. Note that soft-404 pages indexed under their new content are still problematic since most search engines put a substantial weight on anchor text, and the anchor text to soft-404 pages is likely to be quite wrong.

(3) Crawling: Decay score can be used to guide the crawling process and the frequency of the crawl, in particular for topic sensitive crawling [12]. For instance, one can argue that it is not worthwhile to frequently crawl a portion of the web that has sufficiently decayed; as we saw in our experiments, very few pages have valid last modified dates in them2. The on-the-fly random walk algorithm for computing the decay score might be too expensive to assist this decision at crawl-time but post a global crawl one can compute the decay scores of all pages on the web at the same cost as PageRank. Heavily decayed pages can be crawled infrequently.

(4) Web sociology and economics: Measuring decay score of a topic can give an idea of the `trendiness' of the topic.

There are a number of interesting directions for future work -- both theoretical and applied.

On the applied side, it will be interesting to know if there are other decay-like measures that can have applications. For instance, in the context of business intelligence, one such measure can be: following a link to a competitor's web page is like encountering a 404. It will be interesting to study such measures and see if they can be applied in market analysis, etc.

It also might be possible to estimate decay by completely surfing a small neighborhood around the node of interest, say radius two, although a very similar effect can be obtained by setting σ = 0.5.

Furthermore there could be other signals of decay that can be automatically determined (such as HTML level, dates, the use of obsolete slang, etc.) that could be combined with our notion of decay. It would be interested to build a decay classifier and see it it can approach human discernment.

Large search engines and crawlers can keep copies of the crawled content and detect and analyze changes between consecutive versions. However, it is not obvious how to interpret them: frequent changes might represent good maintenance or might be mechanical changes or insertions (e.g., current date). No change might represent abandonment or it might indicate a stable or infrequently changing document (e.g., legislation).

It might be also possible to use the random walk approach to determine the centrality and focus of a given directory with respect to a particular topic. Here the stopping probability should be proportional to the topicality of the page and non-topic page should yield failure.

As we mentioned in Section 2, theoretical study of models for the web graph has focused primarily on page creation, and to a much lesser extent on page death. It has not focused at all on page abandonment, even though model fidelity would be greatly enhanced by doing so. It is will be quite valuable to study decay in an model for the web graph.